UK National & Regional Birds

England & The Robin

The robin is Britain's most familiar and favourite bird. Its popularity as a Christmas card icon dates back to the Victorians. However, its place in English folklore can be traced back to when it was first seen as an afterlife messenger, a symbol of birth, renewal, good fortune and happiness. Whatever the myth or superstition surrounding it, the fiery breast of the robin has captivated the minds of countless admirers for generations.

A welcome garden visitor and typical resident of woodlands, allotments and parks, the robin unofficially remains England’s de facto national bird despite officially becoming Britain's national bird in 2015.

The Gardener's Friend

When defending their territories, robins have a reputation for punching above their weight, the same way one might regard one's home as one's castle, but with a year-round song to say so and prove it.

This sparrow-sized passerine with a bulldog mentality is truly a bird for all seasons, feeding on seeds, fruit and invertebrates. They also have an affinity for freshly tilled soil, where they can easily find some of their favourite foods - worms and insect larvae. However, their real charm comes from allowing themselves to be hand-fed when frequently fed. Hence the nickname, the gardener's friend.

Wales (Cymru) & The Red Kite

In some ways, the story of the Red Kite has followed the fortunes of Welsh identity and the Welsh economy, two particulars with a past comparable to the soaring success of a bird once on the verge of extinction. When red kites disappeared from the rest of the UK two hundred years ago, the few that remained hung on in Wales. Struggling throughout the centuries yet resilient enough to prevail against the odds, the red kite has emerged as a living, thriving symbol of the Welsh language and culture, earning its well-deserved place as the national bird for Cymru in 2007.

The Comeback Kite

Known in the vernacular as The Land of Song, Wales is also the land of the red kite, where hundreds of them can be seen every day at special feeding stations in places like Llanddeusant, Bwlch Nant yr Arian, and Gigrin Farm. Away from the bird tables, these medium-sized raptors prey on small mammals, birds, reptiles, fish and amphibians, but when these become scarce, they resort to feeding on earthworms and carrion. Since their reintroduction in the 1990s, they've made a remarkable comeback. Kite numbers have increased at such a rate they're now the most successful example of species reintroduction in the UK!

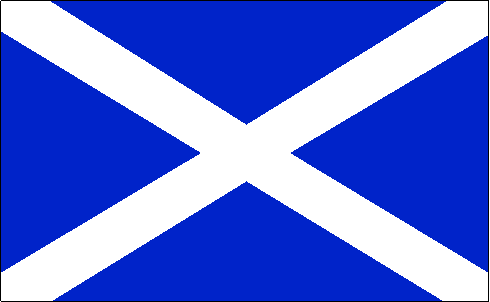

Scotland & The Golden Eagle

Scotland – Britain's last retreat of the golden eagle, owes the beauty of its lochs, glens and moors to her Caledonian landscape, a mountainous landmass with natural borders hosting one of Europe's few remaining expanses of wilderness. Under its Right to Roam Act, Scottish law allows far more access to nature than anywhere else in the UK. Since Scottish freedom comes to full expression within the highest regions of its wilds, there's no bird more fitting and symbolic of Scotland's pride, strength and desire for sovereignty than a sovereign of the air typically found throughout her mountains and isles.

A King of the Sky

Majestic in flight, the magnificent golden eagle is one of our most prestigious birds of prey. Yet nowhere in Britain does it embody the spirit of wilderness more than when soaring the highlands and cliffs, hunting in places few would dare to venture. Although not yet official, this spectacular two-metre wingspan aerial predator is regarded by many as Scotland's national bird. Yet conflict still exists from it taking game birds and livestock, resulting in unlawful persecution. Still, thanks to a particular project, golden eagle numbers in Southern Scotland have improved enough to allow them to reclaim their title and rightful place as kings of the sky.

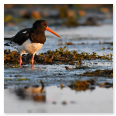

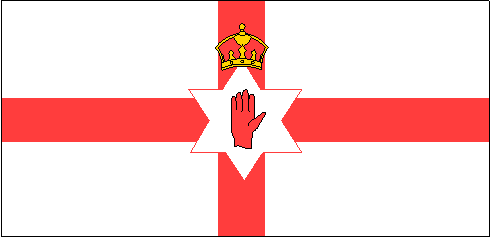

Northern Ireland & The Oystercatcher

Often referred to as a territory or province within the Ulster region, Northern Ireland is a part of the UK bordering the Republic of Ireland. Being a territory with no official symbol, motto or flag, it occasionally uses the Ulster Banner to distinguish itself from the Irish Republic. In 1961, the Eurasian oystercatcher was unofficially selected to represent the region – a fitting choice for its 7,524 km coastline renowned for beauty spots like the Giant's Causeway and a certain wild charm for thousands of migrating waders.

Birds Without Borders

Like a foreign state bordering on an island nation, the oystercatcher is a true anomaly amongst shorebirds. Whereas most wader chicks usually feed themselves after hatching, the oystercatcher is only one of two* British waders to feed its young. In the UK they seldom eat oysters though their diet does consists of shellfish, crustaceans, lugworms, and ragworms. However, as winkles, mussels, and cockles are a source of human food, increasing competition has forced them further inland to fare more on earthworms and snails.

Irish oystercatchers are short to mid-range migrants, and although they tend to stay in Ireland, they hold no truck with borders, territorial waters or restricted air space. Instead, their loyalty comes from where the weather and food sources drive them – albeit back to Iceland or the other side of the divide between the Region and the Republic. As a result of commercial cockle-bed dredging, much has been done on both sides of the border to preserve the loughs, lagoons, salt marshes and mudflats along Ireland's coasts for its wildfowl and waders.

*The other is the stone curlew.